5 Useful Things I learned from Having My Genome Tested

What if someone could look inside of you and tell you exactly what you should be eating?

You could ignore the fad diets, forget about this year’s “low-carb”, “low-protein”, “low-whatever” hysteria. You could graciously step off the “egg” merry-go-round and ignore the persistent rally cries of the “fat in food” debates. You would know exactly what to eat to effortlessly keep your twentysomething physique well into your eightysomethings, your complexion clear, and your mind as sharp as a sherpa’s icepick.

Because you would know your body’s secrets. You could smile smugly with your lean physique and glowing skin, knowing that you were doing the absolute best for YOU, guesswork be gone, forget about following the herd.

Well, that time hasn’t quite come, yet. But it’s certainly getting closer. For, this is the promise of Nutrigenomics.

Nutrigenomics 101

First, a couple of basics: Your DNA is your “genetic blueprint” and it acts as a template for making your proteins. If you have a typo in your DNA, called a single nucleotide polymorphism or SNP (pronounced snip) then the protein made from your genetic code will be a slightly different shape, and this will affect how well it works. This would be kind of like if an assembly line was using a mould to make parts. If the mould, which is a template, was a slightly different shape than normal, then the part made from it would be a slightly different shape and that would affect how well it worked in the machine it was to become a part of.

By knowing which proteins and enzymes we’re not as naturally good at producing, we can add in specific supports via diet and supplements, to overcome the deficits. This is the beauty of nutrigenomics.

Decoding my Genes

Last October, I took the genetic test from 23andme and had my results analysed over at MTHFRSupport for 20 bucks. Through a combination of questioning colleagues and getting my “nerdy researcher chick” on, I learned some practical, actionable information about my “genetic blueprint” that has guided me towards better choices to better nourish my “one of a kind” genome.

Insight Number 1: I would not make a very good vegetarian

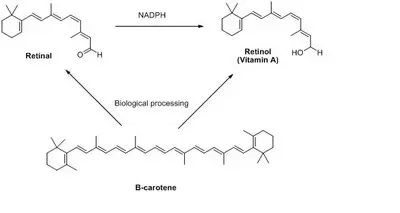

Most people don’t realise that Vitamin A aka “retinol” is only found in animal sources of food. When people talk about the high Vitamin A content of carrots, sweet potatoes and dark leafy greens, they’re really referring to carotenoids, which are provitamin A. You actually need an enzyme to lop off part of provitamin A to make actual vitamin A.1 And it turns out genetically, I’m not too clever at that manoeuvre.

Due to a double-mutation that I share with a quarter of the population on a gene called BCMO1, my ability to convert carotenes to retinol is reduced by 57% and I’m at a much higher risk of turning orange if I drink too much carrot juice (which would be kinda interesting to try).

Insight Number 2: I should be taking probiotics

The analysis also revealed that I have 3 double-mutations on the FUT2 gene, which according to studies has the effect of decreasing the amount of bifidobacteria (a type of friendly bacteria) in my gut.2 This is really handy information to know so that I can make sure I top those levels up with probiotics and fermented foods and monitor my levels through GI testing. Studies have shown that having this mutation increases the carrier’s risk of bowel problems such as IBD3 and bowel cancer. However, if lower bifido levels is the mechanism by which this risk increases, then maintaining optimal levels would be a good way to bring the risk back down again.

Insight Number 3: SSRI’s Wouldn’t Suit Me

The MAO A gene codes for an enzyme that breaks down serotonin so folks with this mutation are susceptible to having elevated levels. I can’t help but think that it would be a good idea to test patients for this mutation as well as neurotransmitter balance before prescribing anyone an SSRI, as it may be this type of mutation that selectively leads to an increase in suicide risk.4

Insight Number 4: I really benefit from a higher consumption of lecithin

This is something I actually knew nothing about until I started looking into all of this. I can best describe lecithin as a yellow/brown sticky goop. It’s a component of certain plant and animals and is very high in something called phosphatidylcholine (PC). We get PC both by producing it in the body and through our diet and it plays a number of roles in the body. It’s a major component of cell membranes and is shown to have anti-inflammatory affects. The “choline” part of phosphatidylcholine is also a precursor to acetylcholine, an important neurotransmitter in the brain.

I actually have a combination of mutations that make having more PC kind of important for me. I have some mutations on the PEMT gene that codes for making PC, which means I’m don’t make as much of it as “normal”. And then I have a couple of mutations on the BHMT gene that means that my requirement for PC is actually higher than most people’s. So I make less but need more.

And I gotta say, since I started taking a PC supplement (made from sunflower seeds), I’ve noticed some nice improvements. My mind feels sharper and I actually dropped a couple of pounds without changing my diet or exercise routine due to its beneficial role in fat metabolism.5 Score!

Insight Number 5: I’m a cheap date at Starbucks

There’s a set of detoxification enzymes that live in your liver that are responsible for helping you break down toxins so that you can excrete them. One particular enzyme, CYP1A2, affects how quickly or slowly you metabolise caffeine. I have a double-mutation that puts me firmly into the “slow-detoxifier” category.

I have to say, this one was no surprise to me at all. I still remember the first time I had caffeine. I was about 5 or 6 and had helped myself to a swig of someone’s Coke when we were out at lunch before anyone could stop me (soda was stricly verboden to me in the 80s). Anyways, this would have been around noon that I had one mouthful of Coke. And let me tell you, I did not sleep a wink that night, no joke. So yes, thank you, trusty CYP1A2 double-mutation for a memorable evening.

I would love to see this SNP screened for in more studies about the effects of caffeine on various disease risks, as I think it might explain some of the confusion about it’s effects. There are piles of research suggesting that caffeine is both very helpful and very harmful (in the right quantities) to human health. Perhaps this SNP explains some of the discrepancies?

Closing remarks

I hope these have been useful examples of the type of practical information you can get from running a genetic analysis and having the results interpreted. My intention wasn’t to ramble on about myself or make myself uninsurable. I just wanted to give you an idea of the types of useful things you can learn from a Nutrigenomic analysis, and this was just the tip of the iceberg.

What a genetic test won’t tell you

But, it’s important to keep the type of information it provides in perspective – a genetic analysis will not tell you if you are sick or well, it will not tell you if you are going to get cancer, or Alzheimer’s or if you are going to keel over from a heart attack tomorrow. It also will not tell you that eating anything other than real, clean, whole foods is ideal for your health, as presumably if you are reading this blog, you have a set of human genes.

What it will tell you

What the analysis does tell you are the areas that are likely to need a bit of extra support. Your actual health and nutrient status can only be confirmed by biochemical tests, not genetic tests. For example, while my ability to convert beta-carotene to Vitamin A is limited due to my genetics, that does not necessarily mean that I am low in Vitamin A and need to rush out and take high dose Vitamin A supplements. Indeed, nutrient testing confirmed that my Vitamin A status was superb. On the other hand, the same test revealed that I was indeed low in PC, which is why it made sense to me to supplement that nutrient.

There’s a saying in this field: “Genetics loads the gun; epigenetics pulls the trigger.” I’d like to add to that idea that Nutrigenomics, the field of assessing genetics and nutrient sufficiency and using these to promote health and wellness on an individual basis, is a way of putting the safety back on any guns you may have lying around in your genes. Which, I must say, is pretty cool and a really smart idea.

What are your thoughts on Nutrigenomics? Please leave your questions, comments, and thoughts below!

1 Tanumihardjo, S. A. (2002). Factors influencing the conversion of carotenoids to retinol: bioavailability to bioconversion to bioefficacy. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. Internationale Zeitschrift Für Vitamin- Und Ernährungsforschung. Journal International De Vitaminologie Et De Nutrition, 72(1), 40–45.

2 Wacklin, P., Mäkivuokko, H., Alakulppi, N., Nikkilä, J., Tenkanen, H., Räbinä, J., et al. (2011). Secretor Genotype (FUT2 gene) Is Strongly Associated with the Composition of Bifidobacteria in the Human Intestine. PLoS ONE, 6(5), e20113. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020113.s001

3 McGovern, D. P. B., Jones, M. R., Taylor, K. D., Marciante, K., Yan, X., Dubinsky, M., et al. (2010). Fucosyltransferase 2 (FUT2) non-secretor status is associated with Crohn’s disease. Human Molecular Genetics, 19(17), 3468–3476. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq248

4 Khan, A., Khan, S., Kolts, R., & Brown, W. A. (2003). Suicide rates in clinical trials of SSRIs, other antidepressants, and placebo: analysis of FDA reports. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(4), 790–792.

5 Detopoulou, P., Panagiotakos, D. B., Antonopoulou, S., Pitsavos, C., & Stefanadis, C. (2008). Dietary choline and betaine intakes in relation to concentrations of inflammatory markers in healthy adults: the ATTICA study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87(2), 424–430.