6 Reasons You Have IBS

6 Reasons You Have IBS

“We couldn’t find anything wrong. All of your tests are normal. You have IBS.”

Unfortunately, these unhelpful words are uttered to millions of people across the globe. There’s little more disheartening than being told that no cause could be found for your painful and debilitating symptoms. And what’s worse, you feel like people think it’s all in your head.

The Real Causes of IBS

The truth is that most of what you’ve probably been told about Irritable Bowel Syndrome, aka “IBS”, is completely untrue. For starters, IBS isn’t really a condition, but rather a collection of symptoms (diarrhea, constipation, bloating, pain, gas) with differing causes.1 You, your friend, your boss and your dog may all have the IBS label, but you might all have completely different things going on that are causing your symptoms.

Another important and damaging myth is that IBS is a purely functional illness -“Sure, you have symptoms, we’re not accusing you of making it up, but when we examine you from head to toe we can’t find a single thing wrong. Perhaps you’re just stressed.” Ugh.

“The diagnosis has mainly been one of exclusion in which IBS was the wastebasket term used to describe what was left after “real” diseases were ruled out” – Rountree 20132

The truth is that people with IBS do have actual physical, measurable differences in their body compared to digestively healthy people that cause their symptoms. But first, we need to remember the first point – IBS isn’t a single condition but a collection of symptoms, and thus the search for a single cause or biomarker is and always will be fruitless. Second, research has shown for some time certain differences in the guts of patients with IBS. But like with any shift in thought, getting the word out and changing minds takes time. This article will give you crucial information based on the latest research about the top physical causes of your IBS symptoms so you can begin to unravel what’s going on in your gut and take action.

Reason Number 1: Your Gut Bacteria are Out of Whack

Your gastrointestinal tract or “gut” is the long tube that runs from your “kisser” to your “keister” (your “pie hole” to your “bum hole”, your “yapper” to your “crapper” . . . but I digress). There are differences in the structure and environment of each part of the gut, depending on its function. And a crucial aspect of each part and how it functions is down to the bacteria that reside there. There are between 10 to 100 trillion bacteria in your gut and these contain 100 times as many genes as your own DNA3. That’s a lot of bugs. And both the number and location of the bacteria of each species play a big role in all aspects of your health, including digestion.

SIBO

Compared to the large intestine, the small intestine should have relatively few bacteria, somewhere in the region of 100-4 4. When this number creeps higher, you have Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth, or SIBO. What are the symptoms of SIBO? Diarrhea, constipation, bloating, pain, gas.

Wait, aren’t those the symptoms of IBS? Yes, yes they are.

And studies show that 31 – 84% of IBS patients have SIBO.5 This is confusing to me, because people with SIBO, as confirmed by a hydrogen breath test or molecular methods, do not have a functional digestive disorder, they have SIBO. Go figure.

Bacteria in the Large Intestine

As opposed to the small intestine, which should be relatively bug free, the large intestine is a hive of microbial activity.

So what’s going on in IBS colons bug-wise compared to digestively healthy folks?

- People with IBS have fewer Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium bacteria6

- There are also differences in Coprococcus, Collinsella and Coprobacillus7

- The number and types of bacteria in the colon of someone with IBS is less stable than controls, it has more of a tendency to change from one day to the next8

So what?

- Gut bugs have a direct effect on gut motility – some speed up transit time, others slow it down9so having imbalanced gut bacteria can cause diarrhea, constipation or a combination of the two

- Gut bugs produce organic acids. Altered gut bugs alter the balance of organic acids and these acids increase sensitivity to pain and distension in the colon10. Levels of acetic acid and propionic acid in particular have been shown to be strongly correlated with severity of IBS symptoms, and those with the highest levels had the lowest quality of life11

- Helpful gut bugs keep unhelpful gut bugs from taking root, so if you’re low on the former, you’re likely to find your colon home to an overgrowth of the latter12

- Helpful bacteria enhance barrier function and prevent the gut from getting leaky13 (see Reason Number 3)

- Lactobacillus and Bifido (the helpful bacteria that are in lower number in people with IBS) don’t produce gas when they ferment carbs but others do, causing you to fart!

(I want to note that I really try to veer away from the terms “good” and “bad” when talking about bacteria – it’s really all about balance)

Reason Number 2: Your Gut is Inflamed

People with IBS have been shown to have an increased number of immune cells, such as lymphocytes and mast cells, in the large intestine.1415 These cells release chemicals (cytokines, histamine, proteases, and prostaglandins) that are designed to knock down infection and help with repair and healing. You know what else they do? They alter sensation and motility in the gut, a bit like what you find in IBS. And what’s more? Studies have shown that patients with IBS had increased markers of inflammation in their gut, even when an endoscopy showed no inflammation.

Reason Number 3: Your Gut is Leaky

The surface of your gut is a bit like a sieve or a piece of mesh with teeny tiny holes in it. These holes allow tiny particles of fully broken down nutrients to pass through while preventing larger particles from going through.

In many people with IBS, particularly diarrhea predominant IBS, the “mesh” of the gut surface has relaxed so the holes are bigger – this is called increased intestinal permeability,16 which means that things like food that hasn’t been completely digested and large inflammatory molecules can pass through the gut wall, triggering a larger inflammatory response.

Reason Number 4: You Have an Infection

This one really gets me. Nearly half of IBS patients have a protozoal infection such as blastocystis hominis or giardia17

And really, if you have a gut infection, then you don’t have IBS, you have a gut infection. Period.

Reason Number 5: You’re Eating the Wrong Food

IBS can be a direct result of food allergies or intolerances.18 Likewise, having IBS, with the altered gut bugs, low grade inflammation, and the changes in intestinal permeability that can go with it, can cause increase immune response to certain foods. About 2/3 of folks with IBS say that certain foods or eating can trigger their symptoms.1920

Restriction of FODMAPs and gluten have both been shown to be successful in reducing IBS symptoms, showing that they play a contributing role in the overall picture.212223

Reason Number 6: Your Neurotransmitters are out of Whack

Most of us are familiar with serotonin, the neurotransmitter that is supposedly deficient in people who are depressed. What few people realise is that most of the serotonin in your body is actually in your gut and is responsible for the coordinated contractions that lead to smooth transit of contents through your GI tract.2425

One of the primary ways that your gut controls serotonin levels is through transporters that mop up serotonin after it’s been released to make sure levels don’t get too high. People with IBS have been found to have fewer of these transporters (called SERT) in their large intestine compared with healthy controls.26 This can lead to too much serotonin being left around, which can increase transit speed and lead to diarrhea. Likewise, the opposite can happen as the receptors down-regulate in response to too much serotonin lying around, leading to slower transit times and constipation (or a combination of the two!).

What causes a decrease in SERT? This situation is partially influenced by genetics but inflammation in the gut (see point number 2) can also cause this to happen.

Bottom Line

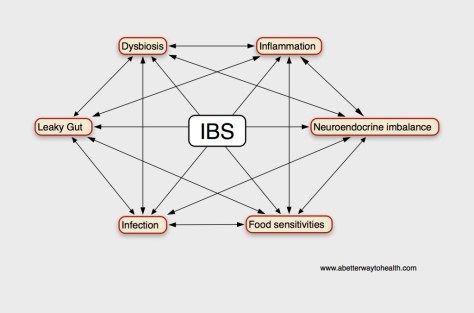

“IBS” isn’t a thing – it’s the result of many different factors coming together in a unique way that varies from individual to individual. All of these physical causes of IBS can lead to the others. For example, dysbiosis can lead to inflammation, leaky gut, and infection. And inflammation can contribute to dysbiosis (and leaky gut and infection and food sensitivities). They are all intimately connected and effect one another.

And it’s certainly not invisible. Hundreds of studies have shown for over a decade that there are real, physical and observable changes in the guts of people with IBS.

Although IBS is considered a functional gastrointestinal disorder, IBS research has recently focused on organic components of causative factors including low-grade inflammation, mucosal immune activation, and altered intestinal microbiota. Lee 201027

If you have been told you have IBS, start thinking like a detective and ask yourself: “What could be causing my symptoms?” But don’t let anyone tell you that “nothing’s wrong” or that “it’s all in your head.” If you currently have a diagnosis of IBS, it just means that no one has figured out what’s wrong yet.

In future posts, I’ll show you how to identify what’s actually causing your symptoms and what you can do to heal your gut. In the meantime, breathe a side of relief. It’s not all in your head.

1 MAWE, G. M., COATES, M. D.; MOSES, P. L. (2006). Review article: intestinal serotonin signalling in irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 23(8), 1067–1076. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02858.x

2 Rountree, R. (2013). Roundoc Rx: A Systems Biology Approach to Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 19(6), 289–295. doi:10.1089/act.2013.19610

3 Gill, S. R. (2006). Metagenomic Analysis of the Human Distal Gut Microbiome. Science, 312(5778), 1355–1359. doi:10.1126/science.1124234

4 Lee, K. J., & Tack, J. (2010). Altered intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(5), 493–498. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01482.x

5 Lee, K. J., & Tack, J. (2010). Altered intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(5), 493–498. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01482.x

6 El-Salhy, M. (2014). Is irritable bowel syndrome an organic disorder? World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(2), 384. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.384

7 Kassinen, A., Krogius-Kurikka, L., Mäkivuokko, H., Rinttilä, T., Paulin, L., Corander, J., et al. (2007). The Fecal Microbiota of Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients Differs Significantly From That of Healthy Subjects. Gastroenterology, 133(1), 24–33. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.005

8 Lee, K. J., & Tack, J. (2010). Altered intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(5), 493–498. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01482.x

9 Lee, K. J., & Tack, J. (2010). Altered intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(5), 493–498. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01482.x

10 Lee, K. J., & Tack, J. (2010). Altered intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(5), 493–498. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01482.x

11 Lee, K. J., & Tack, J. (2010). Altered intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(5), 493–498. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01482.x

12 El-Salhy, M. (2014). Is irritable bowel syndrome an organic disorder? World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(2), 384. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.384

13 El-Salhy, M. (2014). Is irritable bowel syndrome an organic disorder? World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(2), 384. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.384

14 Lee, K. J., & Tack, J. (2010). Altered intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(5), 493–498. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01482.x

15 Martínez, C., González-Castro, A., Vicario, M., & Santos, J. (2012). Cellular and Molecular Basis of Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in the Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gut and Liver, 6(3), 305. doi:10.5009/gnl.2012.6.3.305

16 Martínez, C., González-Castro, A., Vicario, M., & Santos, J. (2012). Cellular and Molecular Basis of Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in the Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gut and Liver, 6(3), 305. doi:10.5009/gnl.2012.6.3.305

17 Boorom, K. F., Smith, H., Nimri, L., Viscogliosi, E., Spanakos, G., Parkar, U., et al. (2008). Oh my aching gut: irritable bowel syndrome, Blastocystis, and asymptomatic infection. Parasites & Vectors, 1(1), 40. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-1-40

18 Rountree, R. (2013). Roundoc Rx: A Systems Biology Approach to Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 19(6), 289–295. doi:10.1089/act.2013.19610

19 Ligaarden, S. C., Lydersen, S., & Farup, P. G. (2012). Diet in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: a cross-sectional study in the general population. BMC Gastroenterology, 12, 61. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-12-61

20 MORCOS, A., DINAN, T., & QUIGLEY, E. M. (2009). Irritable bowel syndrome: Role of food in pathogenesis and management. Journal of Digestive Diseases, 10(4), 237–246. doi:10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00392.x

21 Gibson, P. R., & Shepherd, S. J. (2010). Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 25(2), 252–258. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06149.x

22 Gibson, P. R., & Shepherd, S. J. (2012). Food Choice as a Key Management Strategy for Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 107(5), 657–666. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.49

23 Heizer, W. D., Southern, S., & McGovern, S. (2009). The Role of Diet in Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Adults: A Narrative Review. Yjada, 109(7), 1204–1214. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2009.04.012

24 MAWE, G. M., COATES, M. D., & MOSES, P. L. (2006). Review article: intestinal serotonin signalling in irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 23(8), 1067–1076. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02858.x

25 Manocha, M., & Khan, W. I. (2012). Serotonin and GI Disorders: An Update on Clinical and Experimental Studies. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology, 3(4), e13–6. doi:10.1038/ctg.2012.8

26 El-Salhy, M. (2014). Is irritable bowel syndrome an organic disorder? World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(2), 384. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.384

27 Lee, K. J., & Tack, J. (2010). Altered intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(5), 493–498. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01482.x