Acupuncture, Science based medicine, and UFOs

Dear Dr Crislip,

Thank you so much for your thoughtful response. I know you are a very busy man with many responsibilities and I really appreciate you taking the time to read and respond to my questions, as silly as they might seem to someone as accomplished and prestigious as yourself.

After reading through your response several times, it appears that you had many more questions than answers for me. Imagine that! Perhaps a meeting of the minds over a tipple down at the local is in order (make mine a Malbec). However, as we seem to be separated by an ocean and an entire continent (and my magic carpet is presently down at the shop getting its carburetor replaced), perhaps we can continue discussing this in the present format.

Your questions were instructive, as it helped me identify some really basic differences in our understanding of how humans work. Not just as it concerns Qi and magic and woo (which I just think are the bees knees) but on basic concepts concerning anatomy and physiology, research methods and how much skepticism is too much.

My response is rather long (so many great questions!) but hopefully I can provide some helpful A’s to your Q’s. So please, make yourself comfortable.

Q: ‘Can I call you Mel?’

A: Absolutely, Dr C.

Evidence and Context

Q: ‘So Mel, I would ask the question, what criteria would you use to judge whether a therapy works? Subjective endpoints? Objective endpoints? Personal experience? Careful clinical trials?’

A: Are these the same clinical trials that you said are wrong over half the time? In that case, I wouldn’t assign as much importance to them as you seem to.

But you like nuance so let’s get nuance-y. The criteria by which to judge whether or not a therapy ‘works’ really depends on the clinical situation. Hard endpoints definitely have their place – particularly in emergencies where outcomes are of a boolean nature: you’re either dead or you ain’t.

But for clinical conditions that are in themselves of a subjective nature, like depression or migraine or low back pain or IBS or insomnia or fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue? Particularly when they are idiopathic, as is often the case? For subjective complaints, the subjective endpoints are clearly the most relevant endpoints any way you slice it. The important thing for these patients is not that their blood tests look better or that a scan reveals a change or that you the doctor can deliver the verdict in a deep, solemn ‘science-based’ voice to the patient as to whether or not you have decided they are objectively better. The only outcome of primary importance in these situations is that the patient can honestly say: “I feel better.”

And the Devil is in the detail. You discuss ‘careful clinical trials’ such as double-blind RCTs as if they could prove that an intervention ‘works’ or doesn’t ‘work.’ Careful clinical trials can only provide probabilities and these are limited in applicability to the clinical setting. I’m not saying to chuck ‘em all out or that they don’t tell us anything clinically useful. But a drug only need be shown to induce an improvement in the outcome measure in question compared to placebo in a statistically significant way in order to be stamped with the ‘science-based seal of approval,’ even if:

- most patients don’t benefit

- the outcome measures studied are irrelevant to the patient being prescribed the treatment

- the sample population is different to most real patients so the results have poor external validity1

- the study doesn’t control for factors that we know affect the outcome (like polymorphisms that affect pharmicokinetetics)

- the drug has never been tested with the particular combination of other drugs that a patient is taking and may not have the same effects indicated in RCTs 2

The other important missing ingredient here is context. Even if RCTs testing acupuncture used a treatment that was a good representation of what I and my colleagues do in clinic (which they don’t) and even if the treatment that is being called “placebo control” was actually biologically inert so that it wasn’t providing treatment effects beyond expectation (they almost always aren’t), I would still ask, what are the patients’ other medical options? Particularly in cases where the patient’s complaint is of an idiopathic and subjective nature (digestion, sleep, pain, mood) where organic causes have been excluded, efficacy from acupuncture needs to be compared to standard of care. Where the treatment effect is larger from both acupuncture and ‘acupuncture lite’ than other available options and all of those options have failed (and especially when side-effects are fewer) your argument to not allow your patient to consider acupuncture as an option based purely on your own personal philosophical grounds is absurd and it is (since you asked) arrogant.

The argument that acupuncture somehow keeps people from using ‘real medicine’ simply doesn’t hold water. Licensed acupuncturists in the US and members of the British Acupuncture Council in the UK are trained to spot red flags and have had many hours of training in anatomy, physiology, pathology, and pharmacology. I frequently send patients back to their doctor when I feel that something important has been overlooked.

You say that placebos are unethical because it requires lying to your patient. That’s not the case at all. Any doctor who has a patient who is suffering from migraine or osteoarthritis of the knee or IBS can tell them honestly: there is a treatment that involves the insertion of fine needles in the body. Studies have found that insertion of needles into these points was equally effective as insertion into those points and that both of these groups had an equal or higher response rate than the group who had the treatments you’ve already unsuccessfully tried and with many fewer side effects.

Let them decide if they’d like to try it. Absolutely no lying necessary.

Q: “Mel: How would you interpret the internal mammary artery ligation studies and, more importantly, how would you apply it?

A: I would interpret the studies in context. If the response rate of ‘fake surgery’ was much greater than the effectiveness of any other available treatment option with a small fraction of the complications (in other words, if the risk benefit ratio was better than any other currently available treatments), then I would certainly make it available to patients as an option while doing further research to figure out what was going on. I would also test the assumption that the effects from the control procedure were completely attributable to expectation and not from the well-documented direct physiological responses that are known to be triggered when someone has an incision made (change in cytokine profile, change in hormonal profile, change in autonomic balance, etc). But that’s just me.

Unbiased Scientific Minds Think Alike

After pondering your question about optimal outcome measures above, I started to think about the relative value of subjective vs objective outcome measures in different clinical conditions and the research around osteoarthritis of the knee came to mind. Here’s a condition where you’d think that it’s obvious what’s causing the pain because you can actually see the physical changes in cartilage and fluid build up on a scan, until you consider that most abnormal radiological findings are actually poorly correlated with pain. 3

I was curious if you Science Based peeps had anything to say about acupuncture for OA of the knee and in my travels I came across Dr Hall’s post on The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons report from 2013, where they had concluded that there was strong evidence against using acupuncture due to lack of statistical significant difference between ‘active treatment’ and ‘controls.’ Ever curious, I downloaded the summary of their findings to see on what they had based their pronouncement since Dr Hall seemed to agree that this conclusion was based on robust, high-quality evidence.

They said they had found “five high- and five moderate- strength studies that compared acupuncture to comparison groups receiving non-intervention sham, usual care, or education.”

Studies that did not seem to exist for AAOS include Witt 2005, an n=300 blinding assessed RCT finding superiority of acupuncture over sham, Jubb 2008, an n=102 blinding assessed RCT finding superiority of acupuncture over sham, and others. These are literally the first 2 studies that I found when I did a quick search on Google Scholar. Perhaps they give reasons as to why their search didn’t pick them up in the 1,200 page report.

I took the time to download the five high quality acupuncture trials to see what such a thing might look like (I wasn’t able to get Weiner et al’s paper but this was actually a pilot study for a full RCT that was performed in 2013). Anyways, here’s a quick summary:

- All five trials are RCTs.

- Three of the five trials were testing (your favourite bait-and-switch treatment) electro-acupuncture. One was testing regular old ‘TCM’ acupuncture. And one was testing something called ‘Periosteal Stimulation Therapy,’ which I had actually never heard of. All of these treatments were given the nickname ‘acupuncture’ for short.

- Three of the five trials compared acupuncture to ‘non-intervention sham, usual care, or education’ as advertised above, and two of these studies were comparing two active acupuncture protocols, but these were summarised by the AAOS as being ‘placebo controls’ for short.

- The five studies ranged in the number of treatments given between 6 and 23 – differing by a factor of more than 3. All of these protocols are characterised as ‘acupuncture’ for short.

- In the two studies that gave six treatments, they found that acupuncture was significantly better than control at the first endpoint (7 weeks & 10 weeks respectively) but not at a later end point after treatment had ended. These findings were summarised by the AAOS as ‘not statistically significant.’ On the other hand, the study that provided 23 treatments found that at 8 weeks, acupuncture was significantly better for WOMAC function scores than sham but not in pain score or global assessment. At 26 weeks, however, the acupuncture group had experienced significantly greater improvement in all 3 measures suggesting a phenomenon known as a ‘dose response relationship.’

Who’s getting stuck?

Unlike many pharmaceutical trials that exclude non-responders to make their results look more robust4, at least two of these studies could be characterised as only including ‘non-responders’ – patients who had severe symptoms of a long duration where conventional treatment had been unsuccessful. They weren’t just treating OA of the knee; they were treating OA of the knee in the worst, most recalcitrant cases.

In one of these studies, subjects on average had had symptoms for about 10 years5. These patients experienced significant improvement with acupuncture treatment.

In the other study, patients were having treatment while awaiting surgery. In addition to the acupuncture group achieving significant improvement in their symptoms while having treatment, three subjects cancelled their surgery due to substantial symptomatic improvement6.

Spot the Placebo

I also took a look at some of the so called ‘placebo controls.’ I’m personally of the opinion that in order for an intervention to be considered an inert placebo where benefits would purely reflect expectation, one needs to experimentally demonstrate that the procedure is not having any physiological effect and not just ‘guess’ that it doesn’t. After all, if the active treatment is the insertion of fine needles to stimulate nerve endings, using a control that also inserts fine needles and stimulates nerve endings is problematic, particularly when both are so gosh darn effective compared to regular treatment in clinical conditions like OA of the knee.

This is even more important where the studies used ‘standardised treatment’ – ‘we’ll just use these six ancient osteoarthritis of the knee points’ said no acupuncturist ever. I certainly can’t speak for all acupuncturists, but when I see a patient with OA of the knee, I take a detailed history and then I do this crazy superstitious ritual where I thoroughly examine their knee. The points that I choose for treatment are partly dictated by what the current moon phase is but also dictated by my examination findings of the patient in front of me.

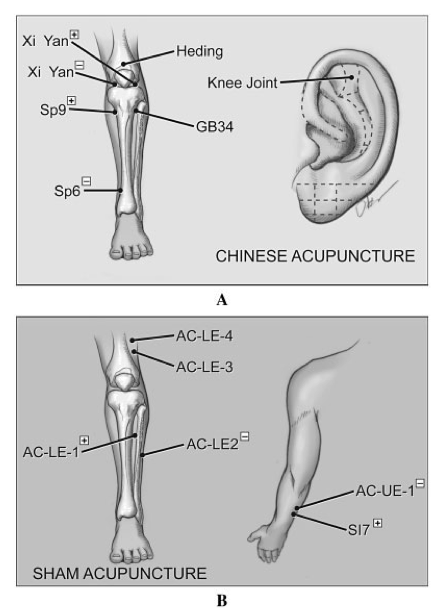

In addition to the well known traditional acupuncture points, many of which have a higher density of certain nerve fibres, there are acupuncture points called ashi points (which is Ancient Chinese for ‘that bloody hurts, stop pressing there!’) which can be located anywhere. The notion of ‘acupuncture points vs non-acupuncture points’ is a fiction invented by those who want to try and study it. The so called ‘non-acupuncture’ points used in the control treatments of one of the studies7, for example, are points that I frequently use with my patients (e.g. AC-LE-4 and AC-LE3 located in vastus lateralis, a common site of inflammation and tenderness in patients with OA of the knee 8).

Let’s needle everyone and see what happens! (Suarez-Almazor et al 2010)

But as to whether the placebo controls were reasonable, I’ll let you be the judge. I thought we could play a little game called ‘Spot the Placebo.’ I’m going to describe three intervention protocols – two of these represent the biologically inert ‘sugar pill’ and one of these is testing ‘real acupuncture.’ Ready?

a) Needling at 6 locations – “Voltage was increased until the patient could feel it and then immediately turned off. Patients rested for 20 minutes with the needles retained, but without TENS stimulation.”

b) Electro-stimulation to acupuncture needles at non-acupuncture points without getting qi sensation for 30 minutes

c) 4 needles located around the knee plus 2 needles just below the knee receiving 100-Hz stimulation for 30 minutes

Well this is tricky. All 3 of these interventions involve electro-stimulation, all three involve at least 20 minutes of needling and two of them involve electro-stimulation for 30 whole minutes!

The correct answer is that “b) Electro-stimulation to acupuncture needles at non-acupuncture points without getting qi sensation for 30 minutes” is being referred to as ‘real acupuncture’ for the purpose of the AAOS review. The other two are the interventions designed to test a purely psychological response to the treatment.

I could continue with pointing out the obvious flaws in these studies and their interpretation but I’d like to focus on some take away points:

- These studies demonstrate a dose-response relationship to acupuncture where those who received more treatment had better response compared to sham and to the other controls. Those who had the least treatment had initial benefit compared to sham and other controls which dissipated after treatment finished, an effect anticipated by one of the study authors who only did such a short protocol due to lack of funding.

- Looking at studies that evaluate ‘acupuncture’ without bothering to figure out what exactly that means (electro or manual, how many treatments (duh!), if the treatment even is acupuncture) is lazy and agreeing with studies just because they support your beliefs is intellectually dishonest

- Looking at studies without identifying what the comparator is (superficial needling, electroacupuncture, active treatment) just because the authors called it ‘a placebo control’ is also lazy and not very scientific

If the position of SBM is to take the moral high road when it comes to scientific appraisal, you need to at least pretend to critically appraise studies when you agree with their outcome. Seriously guys.

I’m also surprised that the good folks at SBM hold these studies up as examples of high quality research into acupuncture. Usually when it comes to electro-acupuncture, you guys say ‘that’s cheating’ faster than a witch can float.

“I was glad to see that the AAOS reached the same conclusions we did on SBM . . . but I wasn’t surprised. After all, we are looking at the same published evidence. Unbiased scientific minds think alike.”

Well, isn’t that just adorable.

Great Expectations

Dr C: Penicillin will cure S. mitis endocarditis every time, whether you believe in germs or not. Acupuncture works best when the patient believes they are getting acupuncture and believes that acupuncture is effective.

Mel: That’s true, but I think we can apply that concept more generally.

Your example of S. Mitis and endocarditis is in the minority of clinical conditions that neatly fulfils something called the Bradford Hill Criteria for causation and as such is one that conventional medicine can actually cure with some consistency. Others include emergencies caused by trauma (if I’m in an accident, Dawkins forbid, do not rush me to the nearest acupuncturist!), and the identification and treatment of inborn errors of metabolism (e.g. avoidance of phenylalanine in PKU).

But how about conditions such as pain, functional digestive illness, or fatigue? The aetiology is rarely so clear and biomedicine’s record at treating these conditions is mixed at best.

So, do beliefs and expectations significantly impact the effectiveness of real, science based pharmaceuticals in these conditions? Or is it only magical treatments like acupuncture?

Well, a 2011 study9 conducted by a team of neurologists looking at the effects of expectancy on the effectiveness of a potent opioid drug found that:

- positive treatment expectancy ‘doubled the analgesic benefit from remifentanil’

- ‘negative treatment expectancy abolished . . . analgesia’

I guess by your definition, if you agree with the design of the study, this proves that Remifentanil is a placebo because its effects were totally dependent on the patients’ expectations. (You may want to rethink your definition)

The effect of expectations applies to your example as well: patients don’t need to believe that penicillin will treat their infection in order for it to ‘work.’ But their expectations for recovery will have a significant impact on how long they stay in hospital and how quickly they’ll return to work. 10

So yes, acupuncture, like all medical interventions, works best when the patient believes it will work. That is not a special feature of magical interventions, as you might choose to believe, but a feature of treating humans, even when the treatment is a ‘reality-based’ one.

Q: So I would ask, as long we are asking questions: Mel, are all 30–40–50 styles of acupuncture (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Ear, Wonli etc. etc. etc.) equally legitimate?

A: You know, I really couldn’t say. I’m not familiar with all of them. Most of the items on your ‘infinite variety’ list aren’t actually different styles but techniques within one style. I imagine you add new treatments to your repertoire from time to time without going through a total change of professional identity?

Q: If all forms of acupuncture are equally effective for all forms of healing and relief of symptoms, then what is the underling mechanism?

A: I think this is what you guys would call a ‘straw man’ argument – saying that acupuncture is effective for some symptoms and conditions is in no way the same as saying that any technique that calls itself acupuncture practiced by any individual is effective for everything. That would be like suggesting that because you support the use of Penicillin for endocarditis that you equally support all medications for everything. That’s just plain silly pants.

A Reality-Based Approach to Disease

Q: “That is one hell of a list Mel. How can needles in the skin have so many effects? What is the mechanism that ties them all together, the one ring to bind them, the commonality underneath acne, schizophrenia, Whooping cough and excess saliva? Or is there a different mechanism for each disease?”

“From my reductionist reality-based approach to disease, each process would require a different intervention. Different mechanisms result in different treatments of the underlying process.”

A: That’s a really good question. Let’s look at another example.

I recently came across a very popular, Science-based treatment. It seemed quite amazing really, because it’s just one single molecule designed to intervene in one particular pathway and it has the following list of effects:

- reduction in pain or inflammation caused by arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, tendinitis, bursitis, gout and menstrual cramps; belching; bruising; difficult or laboured breathing; feeling of indigestion; headache; itching skin; large, flat, blue or purplish patches in the skin; pain in the chest below the breastbone; shortness of breath; skin eruptions; stomach pain; swelling; tightness in the chest; wheezing

And then less commonly:

- Bloating; bloody or black, tarry stools; blurred or loss of vision; burning upper abdominal or stomach pain; cloudy urine; constipation; decrease in urine output or decrease in urine-concentrating ability; disturbed colour perception; double vision; fast, irregular, pounding, or racing heartbeat or pulse; halos around lights, indigestion; loss of appetite; nausea or vomiting; night blindness; overbright appearance of lights; pale skin; pinpoint red or purple spots on the skin; severe and continuing nausea; severe stomach burning, cramping or pain; skin rash; swelling or inflammation of the mouth; troubled breathing with exertion; tunnel vision; unusual bleeding or bruising; unusual tiredness or weakness; vomiting of material that looks like coffee grounds (uh oh!); weight loss

And then in some people, it can cause:

- Anxiety; back or leg pains; bleeding gums; blindness; blistering, peeling, or loosening of the skin; blood in the urine or stools; blue lips and fingernails; canker sores; change in the ability to see colours, especially blue or yellow; chest pain or discomfort; clay-colorer stools; cold sweats; coma (yikes!); confusion; cool, pale skin; cough or hoarseness; coughing that sometimes produces a pink frothy sputum (that does not sound good . . .); cracks in the skin; darkened urine; decreased vision; depression; diarrhea; difficult, burning, or painful urination; difficult, fast, or noisy breathing; difficulty with swallowing; dilated neck veins; dizziness; dry cough; dry mouth; early appearance of redness, or swelling of the skin; excess air or gas in the stomach; extreme fatigue; eye pain; fainting (eh, walk it off, you’ll be fine); fever with or without chills; fluid-filled skin blisters; flushed, dry skin; frequent urination; fruit-like breath odor (taste the rainbow!); greatly decreased frequency of urination or amount of urine; hair loss (hope this treatment comes with a hat!); high fever; hives; increased hunger; increased sensitivity of the skin to sunlight; increased sweating; increased thirst; increased urination; increased volume of pale, dilute urine; irregular breathing; joint or muscle pain; large, hive-like swelling on the face, eyelids, lips, tongue, throat, hands, legs, feet, or (no, not the . . .) sex organs(! Oh the humanity!); late appearance of rash with or without weeping blisters that become crusted, especially in sun-exposed areas of skin, may extend to unexposed areas; light-colorer stools; lightheadedness; loss of heat from the body; lower back or side pain; nervousness; nightmares; no blood pressure (sorry, what does that even mean?); no breathing; no pulse (‘Either this man is dead or my watch has stopped’); nosebleeds; numbness or tingling in the hands, feet, or lips; pain in the ankles or knees . . . (Ok, we’ve gotten to ‘p’ and frankly, I’m a bit bored . . .)

Gee, that is one hell of a list, Dr C! Now, from your ‘reductionist reality based approach,’ you’d think that all of these signs and symptoms would be caused by totally different things, wouldn’t you, not just the ingestion of one itty bitty molecule? And then in your ‘reductionist reality-based approach’ each of these things ‘would require a different intervention.’ And then you’d go treating the skin symptoms with steroids and the reduced urine with diuretics and then the depression with SSRI’s and hope they were just faking the coma. . . you just can’t get enough of that science based medicine!

I mean we have inflammatory effects, cardiac and respiratory effects, lots of symptoms to do with the skin, visual effects, urinary symptoms (both increased and decreased urine output, depending on who was given the treatment), we’ve got some psychological effects . . . And yet, these are all things that can and have resulted from taking just one very popular anti-inflammatory drug (which paradoxically can also cause pain and inflammation!).

I can understand that it’s confusing that blocking one reaction in a particular pathway can have sooooo many possible effects. But in my pre-scientific superstition based training, we have this silly concept where the different systems in the body actually communicate with each other and have a self-regulating effect.

I’d also like to draw your attention to something important: people have different and paradoxical effects to the same pharmacological agent. The pharmacokinetics depends on the biochemistry of the person taking the pill, not on the all the ‘science’ behind the ‘understood mechanisms’ and the average effect beyond placebo in RCTs.

Unlike pharmaceuticals, which utilise exogenous chemicals to stimulate an endogenous effect in an attempt to inhibit or increase a particular biochemical pathway, acupuncture relies entirely on directly stimulating endogenous mechanisms. Understandably, the effects of this will be different in different individuals but this no more demonstrates that acupuncture has no effect than NSAIDs have identical effects on everyone who pops them.

Anyways, let’s go back to your question about how acupuncture works.

Remember when you said that sticking needles into people as part of a treatment “is going to have local effects and effects in the brain”? Apparently, those local effects are of an analgesic and anti-inflammatory nature, as noted previously. That’s supported by the research on purinergic signalling and mechano-transduction studies that I mentioned.

And as for the brain? Well, for a lot of people the brain is pretty important. (I’ll let you decide how applicable that statement is to you personally 😉

Q: “if there is no qi, how does [sic] one process (needles in the skin) . . . effect so many radically different processes? Seems far-fetched to me.”

A: I don’t think it’s really this simple. But putting it all on the line, shot at the buzzer, if I had to name one system through which the experimental evidence consistently demonstrates how acupuncture manages to achieve such a seemingly ‘miraculous’ panoply of effects? I’d go with the neuro-endocrine system11. (Ok, ‘technically’ that may be two systems smooshed together.) Needle stimulation has direct regulatory effects on the hypothalamus, which in turn regulates the endocrine system.

If I was allowed to name another, it would be the immune system (here’s a relatively new study on the role of IL-10 in mediating acupuncture’s effects in mice 12)

Dr C: “Some pharmaceuticals are often overrated in their effects? Water is also wet and fire is hot. The numerous issues with modern medicine and the perversion of clinical trials are a different question. It is the “there are issues with airlines, so let’s use flying carpets” argument.”

If flying carpets got you to your destination at least as reliably and a lot more safely than the airlines, then that would be a half decent analogy. Except that while flying carpet travel doesn’t happen because it defies natural laws, stimulating nerve endings with needles to cause changes in the nervous system with downstream endocrine, inflammatory and visceral effects is a concept that most of the scientific medical community is pretty comfortable with being within the realms of known physiology.

Unhealthy Skepticism

Laugh if you will but I actually consider myself to be a pretty skeptical person. But I think it’s fair to say that we have different calibrations when it comes to evaluating the signal to noise ratio. Your perspective is such that you have an extremely high risk of False Negative Type II error whereas I have a higher risk of False Positive Type I error than you, but probably much lower than the general population.

Here’s the thing: I think you initially wrote off acupuncture because explanations for its mechanism seemed to rely on unnatural phenomena, so you lumped it together with UFOs and the like. This has led you to theorise that acupuncture’s seemingly positive effects are due to cognitive biases shared by billions of people and caused you to entertain huge biases in the way you read and interpret the literature (or whether you read or interpret certain literature at all).

I mean, look: with no detectable sense of irony, you’ve used Ioannidis’ research showing that most published literature comes to incorrect conclusions to support the position that:

1) all positive studies of acupuncture are wrong

2) all negative studies of acupuncture are accurate

3) and yet, even though you agree with Ioannidis’ conclusions, you still profess that you “trust independent studies where bias is removed and the endpoint is not dependent on the whims of the patient and researcher: the double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.” Even though you understand that these ‘independent studies’ have worse predictive power than a freakin’ coin toss, for cryin’ out loud.

You’ve got it bad, Dr C.

The simplest explanation is usually the correct one. Either there’s a world-wide mass delusion, the scope of which is unprecedented in all of recorded history in terms of persistence and the number of people involved, including mainstream biomedical establishments across the globe.

Ooooooorrrrrr:

The therapeutic insertion of fine needles has well-documented neuro-endocrinological and immunological effects that can be clinically useful alongside conventional care. You decide for yourself but honestly? I like you Dr C, but you sound like one of those conspiracy theorists you like to mock, and I know that’s not the look you’re going for.

1 Fortin, M. (2006). Randomized Controlled Trials: Do They Have External Validity for Patients With Multiple Comorbidities? The Annals of Family Medicine, 4(2), 104–108. doi:10.1370/afm.516

2 Frazier, S. C. (2005). Health Outcomes and Polypharmacy in Elderly Individuals. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 31(9), 4–9. doi:10.3928/0098-9134-20050901-04

3 Kornaat, P. R., Bloem, J. L., Ceulemans, R. Y. T., Riyazi, N., Rosendaal, F. R., Nelissen, R. G., et al. (2006). Osteoarthritis of the Knee: Association between Clinical Features and MR Imaging Findings 1. Radiology, 239(3), 811–817. doi:10.1148/radiol.2393050253

4 Broderick, G. A., Donatucci, C. F., Hatzichristou, D., Torres, L. O., Valiquette, L., Zhao, Y., et al. (2006). Efficacy of Tadalafil in Men with Erectile Dysfunction Naive to Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitor Therapy Compared with Prior Responders to Sildenafil Citrate. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 3(4), 668–675. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00273.x

5 Suarez-Almazor, M. E., Looney, C., Liu, Y., Cox, V., Pietz, K., Marcus, D. M., & Street, R. L., Jr. (2010). A randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee: Effects of patient-provider communication. Arthritis Care & Research, 62(9), 1229–1236. doi:10.1002/acr.20225

6 Williamson, L., Wyatt, M. R., Yein, K., & Melton, J. T. K. (2007). Severe knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial of acupuncture, physiotherapy (supervised exercise) and standard management for patients awaiting knee replacement. Rheumatology, 46(9), 1445–1449. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kem119

7 Suarez-Almazor, M. E., Looney, C., Liu, Y., Cox, V., Pietz, K., Marcus, D. M., & Street, R. L., Jr. (2010). A randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee: Effects of patient-provider communication. Arthritis Care & Research, 62(9), 1229–1236. doi:10.1002/acr.20225

8 Levinger, I., Levinger, P., Trenerry, M. K., Feller, J. A., Bartlett, J. R., Bergman, N., et al. (2011). Increased inflammatory cytokine expression in the vastus lateralis of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 63(5), 1343–1348. doi:10.1002/art.30287

9 Bingel, U., Wanigasekera, V., Wiech, K., Ni Mhuircheartaigh, R., Lee, M. C., Ploner, M., & Tracey, I. (2011). The Effect of Treatment Expectation on Drug Efficacy: Imaging the Analgesic Benefit of the Opioid Remifentanil. Science Translational Medicine, 3(70), 70ra14–70ra14. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3001244

10 Mondloch, M. V., Cole, D. C., & Frank, J. W. (2001). Does how you do depend on how you think you“ll do? A systematic review of the evidence for a relation between patients” recovery expectations and health outcomes. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 165(2), 174–179.

11 Cho, Z. H., Hwang, S. C., Wong, E. K., Son, Y. D., Kang, C. K., Park, T. S., et al. (2006). Neural substrates, experimental evidences and functional hypothesis of acupuncture mechanisms. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 113(6), 370–377. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00600.x

12 da Silva, M. D., Bobinski, F., Sato, K. L., Kolker, S. J., Sluka, K. A., & Santos, A. R. S. (2014). IL-10 Cytokine Released from M2 Macrophages Is Crucial for Analgesic and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Acupuncture in a Model of Inflammatory Muscle Pain. Molecular Neurobiology. doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8790-x